At the height of the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic in March, data on the disease was in high demand. It required collaboration — something made more difficult with data lacking in quality.

Having spent most of his career covering politics, last year Rodrigo Menegat realised that science data — particularly Covid-19 data — was fast becoming a staple in the newsroom.

“The first challenge was learning how to cover data which is very different to sport or politics,” he says.

The difficulty was understanding something that, as a country, Brazil was not ready to face.

“One of the main issues is that Brazillian data is insufficient. People were trying to make data as hidden and as unavailable as possible.”

By September he made the decision to leave his newspaper and go freelance.

Rodrigo speaks highly of the work of Nikki Usher. “She said that data journalism allows you to cover other realities.

“You have the far view which is about seeing patterns and connections. Then you have the near view which is how a very complicated issue relates to a specific audience. You can personalise.”

Limited access to Brazilian coronavirus data

With access to data purposefully limited, providing insights and updates was a significant obstacle news outlets in Brazil faced.

Public data was available because of an organisation called Brasil IO. A programmer ran the site with volunteers publishing a database of cases and deaths by the municipalities.

But Rodrigo describes a “political pushback” that meant important portions of information were removed from the website.

But then, he says, the media responded in an “extraordinary” way.

“The newspapers came together and said hey, this is not okay. We, the press, will not allow you to make things less transparent.

“The press felt threatened. Their democratic values threatened. This instinct of collaboration is developing more and the press are still talking about it.”

Debunking and misinformation

In addition to Brazil’s issues with data availability, misinformation is also a problem. Such is the scale of the lack of trust in Brazil that both citizens and journalists doubt even the simplest tweets.

“We need to fight back, and debunking is very important,” says Rodrigo.”

“There is a whole infrastructure for misinformation. People are doing this because they get money through advertisements.

“The work of fact-checkers is important. They are mapping where certain pieces are coming from, who are their supporters and advertisers. Misinformation is being structured so we can see how it plays out.”

However, Rodrigo does not see the use of data as the “cure for all diseases.”

“It is not only about data literacy. There is also something that goes even further.

“This is the feeling of belonging to a political party or group that believes in something. I think that is the main issue of misinformation as people are not actually judging the content. Even people with number and news literacy — they fall for it. There is the issue of making people aware of their biases when consuming information, but this is way more complicated to solve.”

Data and uncertainty

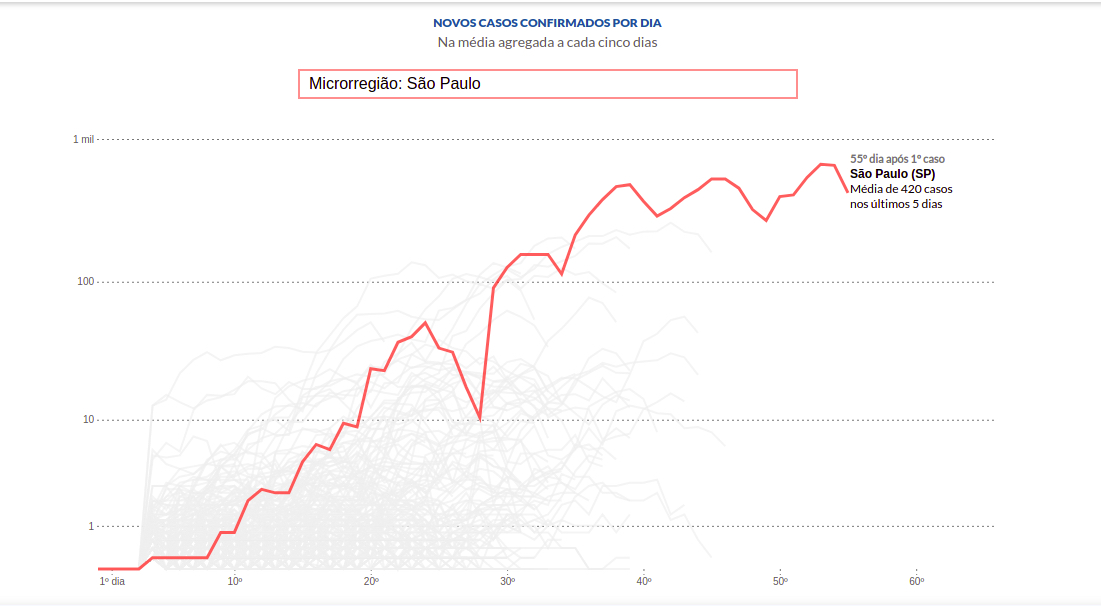

The data in Brazil comes with a plethora of caveats that need accommodating for in any reporting. Whether in a visualisation or a piece of analysis, the data source and limitations need to be communicated.

The data quality issues lead to uncertainty — and managing it “is very complicated,” says Rodrigo.

“The key thing is trying to make people understand that these numbers are the best thing we have.

“The message here has to be that we are working with the best information we can provide you right now. But, you must be aware that it is not as good as we want it to be.”

During the pandemic, assessing how much you can rely on data has become a major focus of data journalism best practice.

In Brazil the administration not only tries to limit the availability of data — it is also often inaccurate.

Data collection occurs at three main levels: federal, state and city. Data is collected at the city level and passed up. As the data reaches the top, reliability comes into question.

“Every state releases data in a different way,” explains Rodrigo.

“Especially in the beginning, there were differences between states and the quality of the data that they released.

“For instance, a city that has a very bad [Covid] situation. The numbers would not be reported back to the states. Systems would even go offline for two or three days in a row to delay the release of the data.”

Data journalism can inform the public, and transparency plays a significant role in achieving this.

When there are doubts over governmental information, journalists can shine a spotlight on some of the flaws. It might be highlighting caveats in the footer, or disclaimers, but the challenge is not to “complexify the message.”

“When there is a problem with the system, we need to add context and being transparent about all the data issues is key,” says Rodrigo.

“We try to give as much context as possible by adding extra layers of information. The data is not perfect. The way tests are being rolled out and even death numbers, they are not reliable. So I think you have to keep in mind all the caveats when communicating uncertainty. However, at this point, we cannot afford to complexify the message.”

The growing prominence of data in newsrooms

The need to display case rates, deaths and movement during the pandemic has highlighted just how necessary data is. And this is not likely to change in the short term: it will be years until the long term effects of the virus are identified.

“I hope after Covid-19 people are a little bit more aware of how data has an impact on our world,” Rodrigo says.

“Journalists used to see [data journalists] as the people crunching data in the spreadsheets. Now, everybody is doing a little bit of data journalism because they need to. I cannot think of a single reporter that has covered Covid-19 without using a spreadsheet.

“If you can find a balance between specialising in complex stuff, and the general knowledge of the craft, this would be a really good thing.”

This piece was published on the Online Journalism Blog.